From Offline to Online Piracy: A Genealogy of Logos

Considering the origins of Logos, the rationale behind each protocol of its technology stack, and its potential to reshape the social order

Jarrad Hope

Diving into the Net

It all started for me at pop-up weekend markets. In Australia, we call them swap meets. Americans call them flea markets. It was often a parking space filled with people selling their goods out of the boots of their cars. What caught my attention were the guys selling shareware and pirated games on cassettes and 5¼ or 3½ inch floppy disks. Using my pocket money, I became a regular customer, eventually learning how to connect to the Bulletin Board Systems from which they sourced their wares.

Around this time, our family moved further into the country. Without physical access to my school friends, I found myself retreating into the net. I spent most of my childhood glued to my CRT screen, my parents complaining they couldn’t use the telephone while our modem whirred away over the line.

As my access to information grew, I discovered Usenet, learned how to set up Direct Client-to-Client, send and receive bots on IRC, and leech from FTP servers. Through ‘the scene’, I found my kindred spirits, patterns of thought I had not encountered in meatspace, and a perspective on the world that appealed to my prepubescent sense of rebellion.

Through this social circle, I began learning the craft of cracking, using SoftICE for cheating games and bypassing licence checks in software. I became aware of International Subversives, created beige boxes at the tail-end of Phreaking, went pit diving, used Telecom’s engineer codes, and entered PABX systems. I eventually began lurking on the Cypherpunk mailing list. There, I became exposed to concepts of cryptography, agorism, counter-economics, Austrian economics, crypto-anarchy, anonymous remailers, and data havens.

What I didn’t realise at the time, except maybe by the faintest of intuitions, was that something deeper was happening. It wouldn’t be much later in life that I would appreciate the connection to piracy, specifically the techniques and tools that cyber-pirates were using.

In The Pirate Organization: Lessons from the Fringes of Capitalism, Rodolphe Durand and Jean-Philippe Vergne argue that piracy drives capitalism’s evolution and foreshadows the direction of the economy, forging paths forward and driving innovation. Operating in grey areas made speed, inventiveness, and agility necessary for survival and naturally challenged the concept of state sovereignty. As their behaviours became formalised and integrated into the system, they expanded the reach of capitalism.

The point is that piracy operates on the fringes of capitalism and the law. This frontier for human activity is one of the most interesting places for creativity and hyper-competition, allowing you to somehow see into the future.

From this perspective, piracy is not something to ‘squash’ or be afraid of; it exposes and exploits inefficiencies in our social systems and ultimately improves its flexibility and adaptability, expanding the frontier, unlocking new modes of commerce, and creating new value.

Virtual Societies and Economic Realities

Being physically isolated, I relied on the Internet for much of my socialisation. I participated in precursors to the ‘Metaverse’ through Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs) and MOOs — multiplayer chats and text-based virtual worlds. By the mid-90s, I was socialising with others in Active Worlds (a precursor to Second Life) and Ultima Online. These programs were primary motivators for me to learn C and write more sophisticated bots.

Because they were microcosms of human behaviour, with similar patterns to meatspace societies, the need for an economy, governance, and property rights manifested itself in very real ways. The case of LambdaMOO is an excellent example, as recounted in the book Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias by Peter Ludlow.

These virtual societies showed me that the mechanisms and institutions for social coordination, created to solve problems and mediate life online, looked similar to their real-world counterparts. In these virtual worlds, social institutions could be rapidly experimented with and deployed, forming new social organisations — a concept I would then learn to be called ‘competitive governance’.

The question became, if real-world institutions worked in virtual worlds, could institutions made for virtual worlds work in the real world? Although enforceability within virtual worlds is much stronger by virtue of being code, I couldn’t see any reason why not.

This idea became more real to me when economist Edward Castronova published the paper ‘Virtual Worlds: A First-Hand Account of Market and Society on the Cyberian Frontier’, showing that virtual worlds like Ultima Online had economies that outcompeted nation-states. Today, we see Big Tech companies commanding more users and revenue than the populations and GDPs of entire countries, lending further support to the notion.

Proto-Sovereign Systems

Relying on a central server architecture, these online institutions remain vulnerable to hostile external forces, as demonstrated by law enforcement’s takedowns of central repositories (i.e., topsites). Consequently, pirates adopted p2p technologies. Protocols and clients like Direct Connect, Napster, Limewire, Edonkey, Gnutella, Soulseek, and Kazaa became the forefront of the scene. Combining the tech with a more straightforward UX made these networks more accessible to a broader audience.

While most of them eventually met their demise (usually through centralised elements of their design), the underlying idea of distributed systems that could be resilient to adversaries, resist coercion, and operate in hostile environments influenced the next generation of p2p technology. This led to BitTorrent, which to this day accounts for three per cent of all Internet traffic.

Upholding Rights with Code

Another approach was to decouple and generalise the activity itself from these p2p communication protocols and strengthen them. This idea is expressed in projects like Tor and I2P, which advocate censorship-resistant and anonymous communication. They do this to uphold civil liberties, such as Freedom of Speech and the Right to Associate, by making networks blind and, therefore, politically neutral to the content flowing through them.

Eventually, this generalisation and complexity became more sophisticated, with projects like Freenet combining messaging, distributed storage, and a ‘Web of Trust’ to form a technology stack that allowed for decentralised applications such as micro-blogging and version control.

GNUNet would take the concept further, providing a software framework and primitives for decentralised applications such as payment networks, decentralised identity, file sharing, and messaging. These networks persist to this day, proving they can uphold their properties sustainably.

In a way, the protocols were material manifestations of a body of thought exemplified by John Perry Barlow’s ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’, Eric Hughes’s ‘A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto’, and Timothy May’s ‘The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto’.

In ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’, Barlow argues that cyberspace is a separate and independent entity created and governed by its users through collective actions. Criticising governments for their lack of understanding and engagement with the online community, he claims they do not have the knowledge or legitimacy to impose their laws and regulations on cyberspace.

Barlow warns against attempts by governments to control or restrict access to cyberspace, arguing that such efforts will ultimately fail in a world where information can be freely shared across borders. Barlow’s conclusion calls for the creation of a more humane and fair civilisation of the mind within cyberspace.

Distinguishing privacy from secrecy, Hughes’s ‘A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto’ argues that the former is essential for the protection of free speech in the electronic age. He suggests that transactions should only reveal necessary information to protect privacy, advocating strongly for anonymous systems.

The manifesto encourages individuals to defend their own privacy and build anonymous technology, with cypherpunks writing code and publishing it for all to use. It rejects regulations on cryptography, asserting that it will inevitably spread globally, and emphasises the need for privacy to be part of a social contract that requires engagement to make networks safer for those seeking it.

In ‘The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto’, Timothy May discusses the potential for computer technology to enable individuals and groups to communicate and interact anonymously.

He explains that this will significantly affect government regulation, taxation, information security, trust, and reputation. The technology for this revolution had existed in theory for a while but was becoming practically realisable with advancements in personal computers and networking.

May acknowledges that the state will try to slow or stop the spread of this technology due to concerns about national security, criminal activities, and societal disintegration. However, he argues that crypto anarchy will inevitably spread and fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and governments. He compares this shift to how printing reduced the power of medieval guilds and how barbed wire altered concepts of land and property rights in the frontier West.

9/11 and the Surveillance State

What made these cypherpunk messages real to me was the orchestration of and response to 9/11. At this point, Western liberal democratic governments unhinged themselves entirely from their people.

Mass surveillance and the surveillance state became ubiquitous, and it was only due to brave whistleblowers that we were even aware of the erosion of our civil liberties. Since then, the capacity and application of Tyranny have been growing steadily, and if ‘we the people’ don’t resist it, it will be too late for our children.

Temporary Autonomous Zones, Virtual States, and Cyber States

In my mid-teens, I got a copy of Cryptoanarchy, Cyber-states, and Pirate Utopias and another book, Virtual States, by Jerry Everard. Along with Bruce Sterling and Hakim Bey — authors of Islands in the Net and Temporary Autonomous Zones, respectively — a growing body of people started to see these parallel threads coming together. As far back as 1988, Leslie Lamport also foresaw what was possible in his paper ‘The Part-Time Parliament’.

These radical thinkers identified the potential for a new order: a new power, a new system that could rival nation-states, one that had the competitiveness, prowess, and adaptability of a pirate organisation, one that was extra-legal and globally accessible — a system that would change the direction of humanity forever.

However, Freenet and GNUnet fell short of using p2p technologies to create practical institutions for the real world. For that, we had to wait for Hashcash and Bitcoin to demonstrate that a separation of money and state is possible. These systems brought to my attention game theory and mechanism design — the bases of crypto-economics and the foundations for much of the innovation to follow.

Bitcoin gave us a mechanism by which we could secure and transmit value anywhere on the net while demonstrating that a distributed system could uphold rights and resist coercion in a hostile environment. It laid the foundations for a virtual world economy that could rival a country's GDP, but its application was in the real world. Crucially, it worked.

Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

In the wake of the 2008 Financial Crash, Occupy Wall Street and Bitcoin demonstrated two forms of protection under Albert O. Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.

The Occupy movement arose from the Arab Spring uprisings, which were themselves precipitated by Wikileaks, another cypherpunk project. Wikileaks was a hack on the state to improve governance through the use of truth bombs that exposed and partitioned the conspirator's social graph, informing citizens of a reality powerful entities would rather keep hidden.

Protesting against the financial elite eventually made its way onto American soil and became known as Occupy Wall Street. This was a time when the Left had an economic argument, wasn’t co-opted by the regime, and wasn’t distracted by identity politics. They took up ‘Voice’ in the form of protest, but the movement didn’t achieve the change it sought and was eventually dismantled by the elites. Organiser Micah White would concede defeat by writing the book The End of Protest.

On the other hand, the peaceful ‘Exit’ strategy offered by Bitcoin has spawned an entire industry that, at its current height, commanded $3 trillion. Here, we see the political potential of our technologies.

Our History: Towards a Real-World Sovereign Stack

It was around 2010 that all of this began to click for me, and I started committing myself to crypto. As groundbreaking as it was — and still is — Bitcoin’s lack of programmability limited its potential applications and, thus, its revolutionary potential. Similar to filesharing and anonymous messaging, we needed to generalise public blockchains. The real magic is creating a decentralised technology stack.

There were attempts to push Bitcoin Script further. Projects like Mastercoin, Counterparty, Coloured Coins, and Namecoin began to surface, hinting at the realisation of Nick Szabo’s idea of ‘Smart Contracts’.

The concept wouldn’t materialise until 2014, when Ethereum was announced. By replacing Bitcoin Script with a virtual machine, you could now have general-purpose smart contracts — i.e., a programmable public blockchain. However, the 2014 vision of Ethereum was widely different than it is today. It promised to be a decentralised technology stack that would, like Freenet and GNUNet, offer private p2p messaging through Whisper and a distributed data store via Swarm.

For me, it was the perfect synthesis of all these ideas; this was the cyber state, the virtual state, the temporary autonomous zone, and I began to contribute to the project in any way I could. I hung out with Jeff Wilcke in Amsterdam to work on Geth; set up the Amsterdam meetup; contributed to the Peer Discovery protocol, Vyper; and participated in countless discussions.

I ultimately ported EthereumJ to Android, and my project, which was an unreleased SPV client called Coinhero, was renamed Syng after the Philip J Syng inkstand used to sign the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, the idea being that you could put that ink into the hands of everyone. The project would later become Status, a WeChat alternative without the state surveillance apparatus.

Something happened to Ethereum that I still haven’t gotten an answer for. After the split of founders like Gavin Woods, Charles Hoskinson, and Vitalik Buterin — and perhaps due to the constraints of the amount of funds raised — the blockchain component’s development took centre stage while progress on messaging and storage stalled.

Status was pretty much the only project using Whisper, so we ultimately took over the protocol’s development and continued building it under the name Waku. Status also relied on a light client protocol, LES, which became dormant, and Swarm, at the time, had project management issues.

We found ourselves incurring more platform risk, and in an effort to build Status, we began moving more into protocol design and infrastructure. We also built out Nimbus as an Ethereum 1 and 2 client, with ‘Fluffy’ supporting the new light client protocol.

Finding no solution for our requirements in decentralised file storage, we started building Codex. And now, given the new attacks on privacy projects like Tornado Cash, Zcash, and Monero, we have a reason to generalise these applications to create a private, neutral, heterogeneous, programmable multichain client. This is the Nomos project.

Ethereum is widely successful, and it continues to innovate. It has the best learning and research community, and I appreciate it for what it is and what it has accomplished. Ethereum has shown us that, like Bitcoin, you can create a more sophisticated economy offering real-world financial services. In its early days, it also showed the potential of a whole myriad of decentralised applications. However, most of them died off as Ethereum wasn’t able to support them.

Logos

Despite its early promise, Ethereum, as a unified, decentralised technology stack, didn’t materialise. The manifestation of a cyber state remains an unrealised, latent cypherpunk dream.

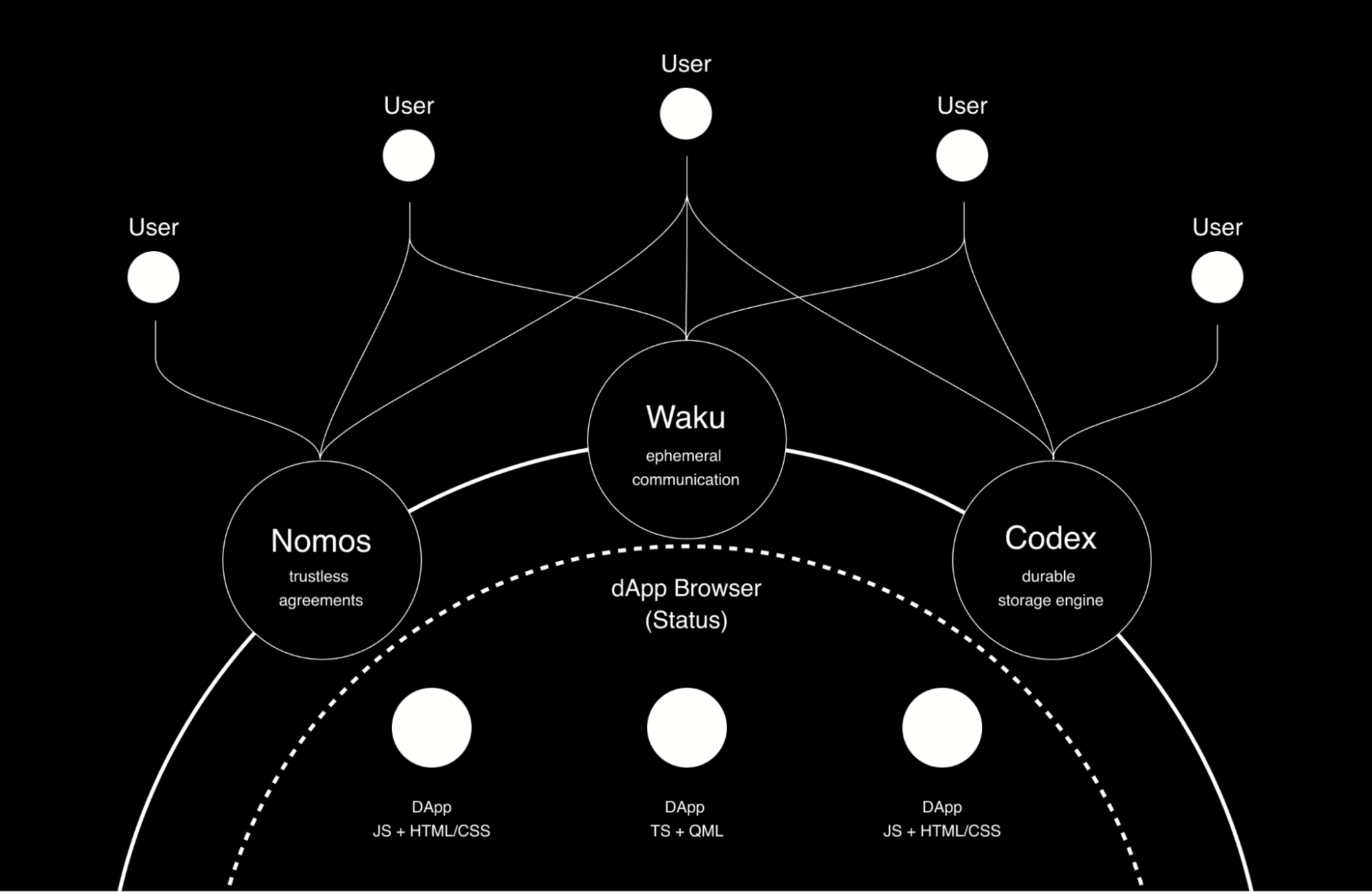

And that’s why Nomos, Waku, and Codex exist. All three protocols represent something novel, but they’re not as interesting alone as they are combined. They come together as Logos. Core primitives in a decentralised technology stack, they strengthen one another in support of a cyber state, virtual state, or network state.

While we recognise each of these projects has independent timelines, the ideal situation is that there is a unified privacy-preserving communications layer (Waku), storage (Codex) is built on top of it, the blockchain (Nomos) state is offloaded to storage, and that consensus happens on the comms layer.

Creating a decentralised technology stack for people to develop censorship- and corruption-resistant decentralised applications is one thing, but its real-world application is where it really shines. It provides a base upon which we can develop stable, fair, and just institutions for anyone connected to the Internet, enabling a new social order by which we can govern our lives.

Eventually, a competitive marketplace of institutions would emerge, filling gaps and addressing costly inefficiencies in governance wherever the net can reach in the real world. The Rule of Law is by far the most significant wealth generator of any country, even over natural resources, as suggested by a World Bank report titled ‘Where Is the Wealth of Nations?’ Therefore, improving governance efficiencies via a fresh approach would lead to greater prosperity for billions of people worldwide.

In short, we’re no longer pirating music and software: we’re pirating institutions and putting them into the hands of those who need them most.

Future

This text is getting a little long. I could write a lot more about the ‘why’, but suffice to say I’ve come to believe this technology, combined with a new ideology, is needed to save threatened political traditions, such as the protection of civil liberties.

Our civilisation has been intentionally (and unintentionally) eroded. We have already seen futile and failed attempts to reform. ‘Exit’ — through the creation of parallel systems — is the most likely viable answer.

If such a system can be realised, it will represent a new political order that is more legitimate than modern liberal democracies, based on the standards with which they defend their own legitimacy.

It can make a stronger case for popular sovereignty and consent of the governed by demanding explicit consent from users. It can enable competitive governance and auto-centric law. Parallel societies can be made with it.

It can manifest an order that isn’t inherently physically coercive. While physical security still needs to be worked out (although I remain partial to a Hoppean-style production of private defence and Friedman-like insurance coverage), it can unlock tremendous value through its application across developed countries, favelas, gated communities, ethnic enclaves, SEZs, charter cities, autonomous regions, neighbourhoods, and proto-states. It is also not as far-fetched as it may appear. Such a system is reminiscent of the Jewish diaspora’s Qahals or Kehillas, a non-territorial ‘State within a State’.

Logos may even have applications as a model for world order. The United States Department of Defense formally recognised cyberspace as a fifth domain of conflict, and the United Nations recognised nation-state claims of sovereignty over cyberspace. These characterisations enable us to conceptualise territory in cyberspace.

If we create a system that can obfuscate network traffic, participants and the code or logic they interact with or deploy can challenge sovereign claims over cyberspace. Suppose you can do it for one nation-state. In that case, you can do it for all, providing a valuable, disintermediated medium for state and non-state actors to join binding agreements while maintaining their sovereignty, should they choose. Moreover, such a system would be blind and impartial to its contents. Upon such politically neutral foundations, we can conceive a monetary policy that may even be suitable for a world reserve currency.

Such an idea is truly awesome, and I hope you will build it with us.

Discussion

Bathang

Logos

Dr. Corey Petty

Peter Ludlow

Jarrad Hope

Peter Ludlow

Jarrad Hope

Peter Ludlow

Jarrad Hope